“My gut hasn’t been right since taking antibiotics,” my patients will say to me in the weeks and months following a course of treatment. As a functional doctor who focuses on holistic gut health, I understand their concern and frustration.

While antibiotics are often a necessary—and even life-saving—treatment, over-prescribed antibiotics are the number one reason for dysbiosis in the gut—an imbalance between good bacteria and bad in the digestive system (1). Not only can the flippant use of antibiotics lead to antibiotic resistant ‘superbugs’, but it can cause patients months of recovery to deal with the collateral damage from an imbalanced gut microbiome.

If you’re on a gut health journey, join us inside the Superwoman Circle to build your complete, personalized road map to a better you—all with the support of an amazing community.

Antibiotics are lifesaving, but not without consequences

Eating, sleeping, passing illnesses, bowel movements and other daily functions naturally cause fluctuations in the microbes that reside in your gut. However, within these fluctuations, your gut still maintains an overall balance.

When you take an antibiotic, this natural balance is disrupted to a much greater extent than the “normal” daily fluctuation. And when your microbiome becomes imbalanced, you’re likely to end up with symptoms ranging from diarrhea and constipation to brain fog and fatigue. Your gut then needs some serious rehabbing to get back to a healthy baseline.

This is because antibiotics don’t just act to kill the bad bacteria causing an infection, but they also kill off the commensal, ‘good’ bacteria that are actually essential to your gut health. For example, one study found that an antibiotic commonly prescribed to treat UTIs, ciprofloxacin, negatively affected about a third of the intestinal microbiome. It decreased the diversity and “richness” of the microbial community (2). Some of these bacteria recovered about a month after finishing the antibiotic, but many weren’t back to baseline as much as 6 months later.

Watch: What Changes Your Microbiome?

How to rebuild your gut after antibiotics — 4 steps

You can implement the following steps while you’re still taking an antibiotic, or after you finish treatment. Following a protocol to heal your gut after antibiotics can help replenish good bacteria and in some cases reduce the likelihood of developing side effects like diarrhea or stomach upset during treatment.

1. During treatment, take a yeast-based probiotic to mediate side effects

Diarrhea is a classic and common side effect caused by the overgrowth of certain bacterial species as a result of antibiotic use. To combat this, you’ll need to look for a specific kind of gut-friendly yeast known as Saccharomyces boulardii (This is also the kind of probiotic you’ll find in my gut health formula, Belly Fix).

Diarrhea is a classic and common side effect caused by the overgrowth of certain bacterial species as a result of antibiotic use. To combat this, you’ll need to look for a specific kind of gut-friendly yeast known as Saccharomyces boulardii (This is also the kind of probiotic you’ll find in my gut health formula, Belly Fix).

S. boulardii has been shown in multiple studies to protect the lining of the intestines from the type of damage that occurs as a result of a dysbiosis, which can lead to leaky gut and all its associated symptoms (3). S. boulardii has also been shown to protect against the development of C. diff infection, which can sometimes occur after antibiotic treatment (4).

Look for a Saccharomyces boulardii with a potency of at least 10 billion CFUs (a measure of the active organism present in the capsule). This type of probiotic can be taken each time you take your antibiotic.

Read: The Guide to Improving Gut Health

2. Take a high-dose, bacteria-based probiotic

Now to help your gut replenish some of the good bacteria lost when taking an antibiotic. Look for a high dose probiotic with multiple strains and at least 50-100 billion CFUs (10-20 billion for children). The best time to take a probiotic during your course of antibiotics is about 4 hours after you take an antibiotic dose.

For example, if you have to take an antibiotic twice per day, do so in the morning and evening. During midday, take a high dose probiotic.

While a probiotic taken during an antibiotic likely won’t colonize new bacteria, taking a probiotic can provide a protective effect against antibiotic side effects such as stomach upset and diarrhea (5).

You’ll take this S. boulardii + 100 billion CFU probiotic regimen throughout the course of your antibiotic treatment. Then, once you’re done with your antibiotic course, you’ll continue the same regimen for one to two months to help your gut continue to recover.

Choosing a Probiotic? Here’s Which Ones are Best for Hormones, Weight Loss, and More.

3. Eat more prebiotic foods

Prebiotics come from dietary fiber, and their primary role is to fuel healthy gut bacteria in the colon (6). When the probiotic bacteria in your gut consume these fibers, they produce unique nutritional by-products that protect and nourish the bacteria in your microbiome.

At the same time that prebiotics are busy stimulating good bacteria, they’re also fermented in the gut to create short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which fuel good bacteria in the gut. SCFAs also play a role in immune health and support healthy barrier function in the gut (7).

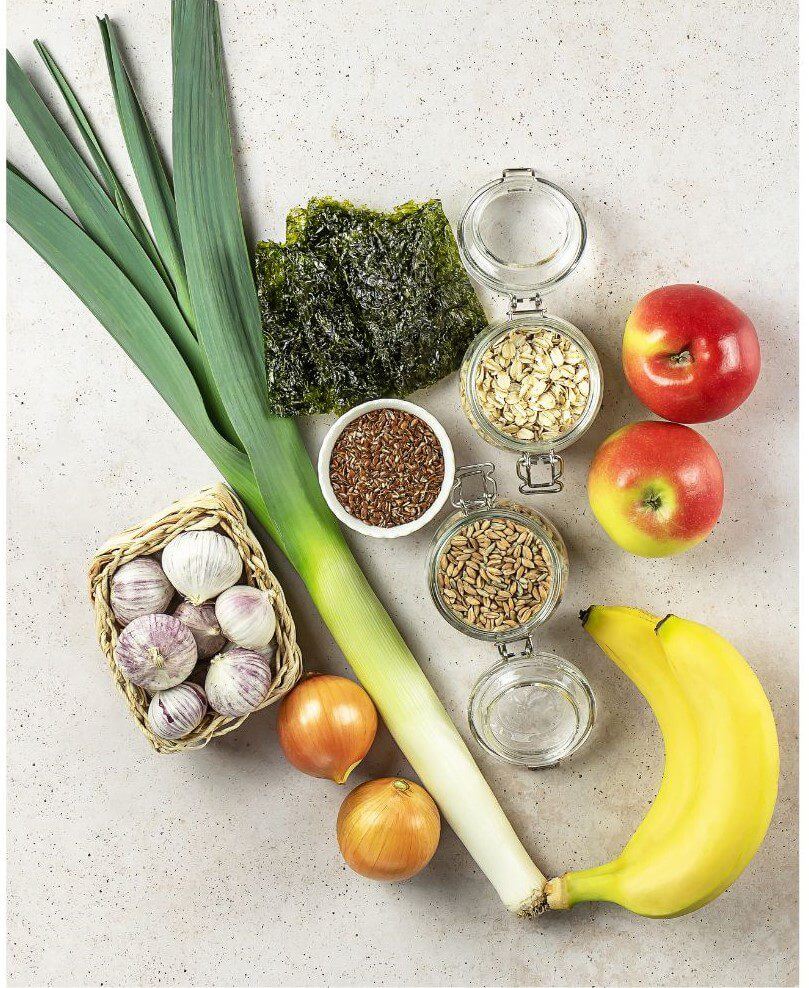

Eat more of these foods for good sources of prebiotic fiber:

- Allium vegetables, including onions, garlic, leeks, and chives

- Apples

- Asparagus

- Cocoa

- Dandelion greens

- Squash

- Green bananas

- Ground flaxseeds

- Jerusalem artichoke

Related: Fiber Making You Bloated? Do This to Avoid the Gas But Keep the Benefits

4. Add fermented foods

While your gut will likely (eventually) recover the good gut bacteria after taking an antibiotic, the main struggle is restoring diversity—or the different strains of bacteria. Probiotic supplements can be incredibly helpful for preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhea and lowering the risk of a gut infection, but probiotic and prebiotic supplements alone generally aren’t able to achieve the optimal level diversity of an entire human microbiome.

So to boost diversity, look to fermented foods, like:

- Kefir

- Cultured milk or yogurt

- Miso

- Beet kvass

- Sauerkraut

- Kombucha

- Kimchi

Store-bought products like yogurt and kefir generally only have a couple of bacterial strains, so if you’re able to make these products at home it can be highly beneficial for your gut.

Try these! 7 Foods for A Healthy Gut

5. Protect from leaky gut

Antibiotics can harm the lining of the intestines, contributing to digestive issues like inflammation and leaky gut. Because the gut lining acts as a barrier to harmful microbes, if it becomes “leaky” it can make you more susceptible to secondary infections afterwards. To support intestinal barrier integrity, consider:

Increasing collagen intake from supplements or food, such as bone broth. Collagen makes up the connective tissue which is literally the “glue” that holds your body together. Your gut uses collagen to maintain the lining that separates your gut from the rest of your body.

L-glutamine. This amino acid helps repair your gut and reduce intestinal permeability (leaky gut) after antibiotic treatment (8). L-glutamine can also help modulate intestinal inflammation by supporting your immune system located in your gut (9).

Watch: How to Heal Leaky Gut Naturally (My Secret Recipe)

Healing your gut naturally after antibiotics

If a doctor prescribes antibiotics, it’s probably for a good reason. Antibiotics are important for bacterial infections like urinary tract infections (UTI), pneumonia, strep throat, mastitis, and more. But they also cause damage to the complex ecosystem that resides in your gut and that helps keep you healthy. Side effects are usually caused by the destruction of good bacteria along with bad during treatment. While you always want to fully complete your course of antibiotics to make sure the infection is gone, you can work on protecting your gut at the same time. Then, after the course of antibiotics is over, continuing to follow a gut-healthy protocol will help replenish the bacteria lost while taking an antibiotic.

Resources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5725362/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19018661/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02624.x

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30881353/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8183490/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6463098/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2018.01354/full

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PII0140-6736(93)90939

- E/fulltexthttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10600341/